New York Times

November 19, 2003

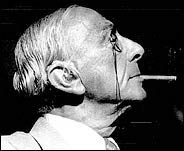

Fritz Kraemer, 95, Tutor to U.S. Generals and Kissinger, Dies

By MICHAEL T. KAUFMAN

Fritz Kraemer, a refugee from Nazi Germany who tutored generations of America's leading generals in historical and geopolitical thinking, died in Washington on Sept. 8. He was 95.

|

| Fritz Kraemer struck up a friendship with Henry Kissinger when the two, fellow German refugees, were privates in the United States Army. |

From 1951 until his retirement in 1978, he worked in the Pentagon as a senior civilian counselor to defense secretaries and top military commanders. His son, Sven, a Pentagon official, said that Mr. Kraemer's title often changed but that he occupied the same map-covered office from which he would be called on to prepare briefings, often on short notice, on such diverse subjects as political developments in Southeast Asia, economic prospects in China and French views on nuclear weapons.

But his influence on national policy was felt most visibly, perhaps, in a friendship he struck in 1944 when he was a private at a Louisiana Army camp during World War II. There, he met Henry A. Kissinger, also a private and another refugee from Germany, whom he helped guide toward a career that reached the highest echelons of government.

In cold-war years, long before Mr. Kissinger moved from Harvard to the office of secretary of state, Mr. Kraemer pursued his antitotalitarian views, participating in formal and informal seminars at staff colleges and within the Pentagon, where Donald H. Rumsfeld referred to him as "a true keeper of the flame."

He also developed close and mentoring relationships with many officers who either occupied or would rise to powerful positions, among them, Gen. Creighton Abrams; Gen. Alexander M. Haig Jr.; Gen. Vernon A. Walters, who later served as ambassador to the United Nations; and Maj. Gen. Edward G. Lansdale, the theoretician of counterinsurgency.

Born in Essen in 1908, Fritz Kraemer was the son a prosecutor and an heiress. A man of conservative instincts, with a veneration for history and culture and a devotion to his Lutheran faith, he acquired doctorates in economics and law. During the turbulent early 1930's he often joined in street battles against both black-shirted Nazis and Communist toughs, holding high the flag of the old Hohenzollern monarchy.

In 1933, he left Germany to work as a legal adviser for the League of Nations in Rome, and he wrote eight books on international law. Having observed fascism in both Italy and Germany, he fled to the United States in 1939 on the eve of war.

Once in the American Army, he cut an eccentric figure, habitually wearing a monocle and carrying a riding crop while speaking loudly in a strong German accent.

At Camp Claiborne in Louisiana, his demeanor attracted the attention of Maj. Gen. Alexander R. Bolling, the commanding officer of the 84th Division, who assigned him to his headquarters.

Walter Isaacson, a Kissinger biographer, said that "Privates Kissinger and Kraemer first met at the camp, when Private Kraemer, speaking from his jeep, delivered a lecture on the philosophy of the Nazi state and the necessity of its defeat to men who had just finished a 10-mile march. The 20-year-old Private Kissinger was stirred and wrote Private Kraemer, saying: 'I heard you speak yesterday. This is how it should be done. Can I help you in any way?' "

Mr. Kraemer looked up the younger soldier and, impressed by his intelligence, gradually inspired and abetted him. As Mr. Isaacson wrote: "Kraemer's patronage was to prove momentous. During the next three years, he would pluck Kissinger out of the infantry, secure him an assignment as a translator for General Bolling, get him chosen to administer the occupation of captured towns, ease his way into the Counter-Intelligence Corps, have him hired as a teacher at a military intelligence school in Germany and then convince him to go to Harvard. Kraemer is often described as 'the man who discovered Kissinger.' He thunders: 'My role was not discovering Kissinger! My role was getting Kissinger to discover himself.' "

Mr. Kraemer was captured in the Battle of the Bulge. Soon after he was taken, he convinced his German captors that an Allied victory was imminent and persuaded them to surrender themselves and the town to him. For this he received a Bronze Star and a battlefield commission.

Mr. Kissinger has written that "Fritz Kraemer was the greatest single influence in my formative years." He cited the conversations the pair had had as they walked battle-scarred streets. The older man, he wrote, "spoke of history and postwar challenges in his stentorian voice, and awakened my interest in political philosophy."

The relationship that Mr. Kraemer and Mr. Kissinger forged at Camp Claiborne endured for years before it deteriorated in 1975 when Mr. Kraemer expressed disapproval of the policies of détente with the Soviet Union that were being pursued by Mr. Kissinger and the Ford administration. The two did not speak for 28 years until last year, when Mr. Kissinger telephoned his old mentor.

In addition to his son, Mr. Kraemer is survived by his daughter, Madeleine Bryant of Cockeysville, Md.; and three grandsons.

Home