Implantable Medical ID Approved By FDA

By Rob Stein

Washington Post Staff Writer

Thursday, October 14, 2004; Page A01

A microchip that can be implanted under the skin to give doctors

instant access to a patient's records yesterday won government

approval, a step that could transform medical care but is raising

alarm among privacy advocates.

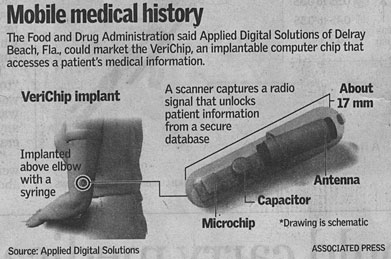

The tiny electronic capsule, the first such device to receive

Food and Drug Administration approval, transmits a unique code

to a scanner that allows doctors to confirm a patient's identity

and obtain detailed medical information from an accompanying

database.

Applied Digital Solutions Inc. of Delray Beach, Fla., plans to

market the VeriChip systems -- the chips, scanners and computerized

database -- to hospitals, doctors and patients as a way to improve

care and avoid errors by ensuring that doctors know whom they

are treating and the patient's personal health details.

Doctors would scan patients like cans of soup at a grocery store.

Instead of the price, the patient's medical record would pop

up on a computer screen. Emergency room doctors could scan unconscious

car accident victims to check their blood type and medications

and make sure they have no drug allergies. Surgeons could scan

patients in the operating room to guard against cutting into

the wrong person. Chips could be implanted in Alzheimer's patients

in case they get lost.

"In hospitals today, many deaths occur because people aren't

able to communicate timely enough their medical information or

because of wrong information," said Scott Silverman, the

company's chief executive. "With VeriChip, you'll be able

to have accurate information even if a patient can't talk. It's

a way to modernize our antiquated system of medical records."

The approval was immediately denounced by privacy advocates,

who fear it could endanger patient privacy and mark a dangerous

step toward a Big Brother future in which people will be tracked

by the implants or required to have them inserted for surveillance,

identification and other purposes.

"Once the technology is out there and is available, it raises

the very real possibility that people in a position to require

or demand it will begin to do that," said Katherine Albrecht,

who has campaigned against such devices. "It would obviously

be possible to inject one of these into everyone. In the post-9/11

world, we are already racing down the path to total surveillance.

The only thing missing to clinch the deal has been the technology.

This may fill that gap."

The VeriChip technology was developed to track livestock and

has been implanted in about 1 million cats and dogs to identify

lost or stolen house pets. But the technology has a variety of

other potential uses, and the company has already sold about

7,000 chips for human use, about 1,000 of which have been implanted.

Mexico's attorney general announced in July that he had one of

the devices injected into his arm, as had about 160 of his lieutenants,

to control access to high-security offices. In bars in Amsterdam

and Barcelona, patrons can have the chips implanted to allow

them to enter exclusive areas and keep track of their tabs.

The company is investigating other applications, including using

the chips as "electronic dog tags" for soldiers, creating

"smart guns" with built-in scanners that ensure they

can be fired only by someone with a corresponding implant, and

enabling stores to verify a customer's identity before accepting

a credit card.

"That same scanner in a Wal-Mart that is used to bar code

your goods can be used to identify you when you present your

credit card to make sure someone hasn't stolen it and your identity,"

Silverman said.

Spurred by South Americans seeking ways to trace kidnap victims,

the company has also developed a device that allows satellites

to pinpoint a chip's location, but it has no immediate plans

to market that gadget.

The company hopes the FDA approval, however, will speed the proliferation

of the chips for medical and other uses.

"We believe that this application is going to drive acceptance

of the product," said Angela Fulcher, vice president for

marketing and communications. "If you have a chronic disease,

where getting information to health care providers quickly may

mean life or death, that population is going to be more accepting

of this technology."

The company hopes to kick-start use of VeriChips by donating

about 200 of the $650 scanners to trauma centers. The chips,

which are the size of a grain of rice, will cost about $200 apiece.

The devices are injected with a syringe under the skin of the

upper arm in a quick, painless procedure.

The accompanying scanners and software ensure that the personal

information unlocked by the 16-digit code is only available to

those designated by the patient, Silverman said.

"Even if people access your unique identification number,

which would be extremely difficult to do, it doesn't give them

access to your database. We're confident in the security measures

we've taken," Silverman said.

Opponents argue that the medical benefits are marginal at best.

Patients can already wear bracelets that alert doctors to their

identities and special medical needs, and few medical errors

are actually caused by patients being misidentified, they say.

But the potential for abuse is great, they caution.

"Over the long haul, any place where there's a surveillance

camera today, five or 10 years from now will have these . . .

readers. You'll walk into a 7-Eleven, and they'll take your picture

and scan your number," said Richard M. Smith, an Internet

security and privacy consultant in Boston. "If we start

carrying these tags it makes a perfect way, either by private

security companies or the government, to keep track of us."

Marc Rotenberg, executive director of the Electronic Privacy

Information Center in Washington, said he was concerned that

people might be forced to get the implants.

"When you put an identification tag under a person's skin,

you make it impossible for a person to remove the tag, much like

branding cattle," Rotenberg said. "The most likely

applications would involve prisoners and parolees, and perhaps,

one day, persons in the United States who are not citizens. I

think there needs to be some legislation put in place to prevent

abuse."

Silverman dismissed the concerns, saying abuse would be technologically

difficult and the benefits would far outweigh any theoretical

risks.

Home