Toward the end, Jones slipped

from reality into fantasy world

San Jose Mercury News - November 29, 1978, front page

Last of a series

By Pete Carey

Staff Writer

JONESTOWN, Guyana -- Toward the end,

the Rev. Jim Jones was two men -- the man he thought he was and

the man he had become.

Surrounded by a following that, through

fear and increasing dependence, showered him with personal attention,

Jones slipped away from reality.

Maybe there never was a solid reality

in the rain forests for a fast-talking minister-hustler from

Lynn, Ind., who expanded his vision to Indianapolis, Ukiah and

then San Francisco before moving on to Guyana.

Jones increasingly used drugs, and as

the morphine oozed through his veins he stumbled around his empire

in a daze.

"I watch your pain and it tears

me up," wrote Tish Leroy, a key committee member at Jonestown.

Her thoughts were in a self-analysis sent to Jones in May or

June of this year.

"You complain that we watch your

every move and judge you -- and it's true," she wrote. "Certainly

I am guilty of that . . . I make allowances for what I see you

doing that seems other than it should be, and on the other hand

I watch your pain and it tears me up inside."

Nearly all of the approximately 1,000

members of the camp had watched their "father" with

growing concern after he arrived with his flock in June 1977.

By that time his paranoia was full blown.

Alarmed at media investigations of his organization and consumed

with hatred for the United States, he finally decided to leave

for the South American jungle hide-away he had first heard about

in 1961 in an article in Esquire. It was written when The Bomb

was the monster and sudden death by nuclear blast appeared to

be the human race's most likely post mortem.

There were nine places in the world,

according to the magazine, where it would be safe to live in

an atomic war. One was Guyana.

"He told me he had been thinking

about coming to this place for 16 years, and he showed me on

a map," said Richard Clayton, one of the survivors of the

final cyanide-laced Kool-aid holocaust. "I think he had

this planned out all the time."

Now, after the bloody extinction of a

sect that was 80 to 90 percent black, Clayton thinks Jones may

have been a secret racist determined to enslave and kill as many

blacks as he could.

There is no question that the hierarchy

of Jonestown was designed along racial lines.

But was he designing a plantation or

was he simply a demented man whose beliefs had begun to twist

crazily -- a philosopher of death holding a knife at the throat

of his students?

"Hey, man, I don't know the answer

to that," said another survivor, Robert Paul. "All

I know is I was a field nigger."

Blacks held the laboring jobs in Jonestown

and whites had the office jobs.

"He really only trusted whites,"

said Juanita Bogue, a 21-year-old survivor who was one of two

whites out of 75 persons who worked in the fields. Her sister

was the other.

"If a black person accused a white

person of being a racist, the way Jones responded would make

you think he was a racist himself. His most trusted workers in

the radio room, the office, were all white. It seemed like he's

pit the whites against the blacks."

On one of his harangues, with the

flock assembled in the meeting area they had constructed, Jones

would argue that whites should be consumed with guilt because

they had made the blacks suffer. At the same time, he'd say that

his best workers were white.

"To me, that was pushing racism,"

said Ms. Bogue. But there was no objection.

"People thought Jones could read

their minds," she said. "When they passed by him, they

would put all the bad thoughts out of their minds, so he wouldn't

know. You have to understand that there were some fairly simple

people out there."

Once he arrived in Guyana, as best as

can be determined, Jones never left his jungle empire. He had

drawn a crowd with religious proclamations on the steps of a

Georgetown Catholic Church when he first arrived, had met with

people in the Guyanese capital, and then had left for the interior

and Jonestown.

Through the window of a plane droning

over Guyana's northwest section the eye takes in two colors:

blue, the sky, and a deep green, the jungle. It is thick, and

stretches away for miles. The little cleared strip at Port Kaituma,

where U.S. Rep. Leo J. Ryan and his party arrived to touch off

the beginning of the end, appears as an island. There is no escape.

Jones apparently wanted it that way to control his flock.

The combination of isolation and power

did strange things to Jones. His sect had always meted out discipline.

At Redwood Valley near Ukiah, infractors had to strip nude and

swim across a pool in front of the congregation. In San Francisco

there were beatings -- and rumors of worse.

But in Jonestown the discipline became

an end in itself.

"They never did kill anybody, but

they'd torture the hell out of them," said Paul.

"You didn't have n freedom. You

couldn't leave, and if you talked about it you'd get a beating

and be put on public service," one of Jones' punishments.

Gerald Parks, 45, from Suisun, recalls

a tour of public service. "The crime was talking about the

United States, and about going back to it. I really got hammered

for it, and then they put me on public service."

Parks was dragged out of bed at 5:30

after sleeping on the floor in his little jail, and his assignment

was digging ditches under guard -- all day long, without a break.

"You couldn't raise up to rest,"

he said.

Behind it all was Jones' need to build

a productive society. He wanted more and more from his people,

and he got it. The incredible fact is that Jonestown, with its

$7 million is assets, was constructed in less than 6 months,

starting in August 1977.

The work left people exhausted. As the

village took shape they would struggle back to camp and eat,

listen to Jones lecture for the evening, do whatever else he

bid them, and then fall exhausted into bed.

The most skilled carpenters in the

community built their leader a house. Down a meandering garden

path, away from the community, Jones could sit in it and pore

over his files, use his drugs, dream up new fantasies to practice

on his flock, and meet with his male and female lovers.

It had a screened porch, an unthinkable

luxury in a community where people were housed 14 to a room in

10 by 12 foot cottages.

Isolation, power and worship. Jones used

the combination to create fantasy.

"The first time I saw you, Father,

I knew my life would be changed," wrote one young woman

camp member. "I was caught up by a ray of sunshine, filled

with gold dust motes, as warm and comforting as honey, was literally

saturated with it, found myself above the congregation, turning

in this warm ray of love . . . thank you, Father, thank you for

the freedom I feel."

Jones began to brag to his followers

that some of them were begging him for sexual favors. He had

to grant them, he said, but only to keep them from leaving.

Gerald Parks recalled that "all

of us had to admit to being homosexuals. Then we found out it

was him. He was going with guys. The leaders of the whole show

were his lovers, and they'd brag about it right up front to us."

Jones began to lecture the group about

the virtues of homosexuality. He urged people to pair off with

persons of the same sex, explaining that it didn't produce babies.

The sexual politics of Jim Jones reached

a crescendo during one camp meeting when, seated on his throne,

swathed in blankets that even covered his head, he announced

that a man who worked as a mechanic and a young woman who worked

in the bakery had touched one another.

"We weren't supposed to have a relationship

without clearing it through a screening committee first,"

recalled Ms. Bogue. "Most people didn't pay any attention

to that, and the main thing was that no one had any time for

relationships. After working in the fields, attending meetings,

and going to lectures, all you had time to do was fall in bed.

"At any rate, these two people were

called in front of everyone. Jones said they had been seeing

each other. Apparently someone saw the boy over at the bakery

and had reported that the girl had given him a cookie. That became

a big rumor, and pretty soon people were saying they were in

love. The funny thing about it is that they weren't. They hardly

knew each other.

"But Jones wouldn't hear that. He

said if they were so excited by each other, they could make love

right here and now. They brought in a mattress, made them take

off their clothes and get down on it, but it didn't work."

In the isolation of his jungle empire,

Jones had begun to use his people like playthings. He toyed with

them, these simple people with only a rare high school graduate

among them, telling them ghostly stories about the world outside

and tightening discipline with rough twists of the screw.

His handpicked guards carried guns around

the camp. People were forced to conform to every thought that

Jones proclaimed.

Meanwhile, Jones was lost in a cloud

of pharmaceutical vapors. The camp began to smell like a drug

cabinet.

Fluttering in the muck of the meeting

hall a few days ago was a tiny corner of paper with a note jotted

on it. The paper had been used on one side to answer a quiz on

a socialist revolutionary activities.

"1. Fifth anniversary, Allende.

. . . 2. Socialist destabilize. . . . 3. French guillotine. .

. . 4. Organized rebellion in Nicaragua."

On its back was the note, probably passed

to someone at the meeting:

"I keep smelling a whiff of formaldehyde.

Do you have any idea where it might come from? Jack."

The last chapter of the Jonestown

story really starts 150 miles to the south, in a Georgetown courtroom,

where a case was brought by Grace Stoen, who had fled Jonestown

without her child, John. She wanted him back. But Jones believed

he was the child's father and said he would die rather than give

him up.

In early September, legal proceedings

began.

On Sept. 9, horns and sirens ripped through

a muggy jungle day and guards with guns ran through the camp,

ordering everyone to meetings.

A wild-eyed Jones faced his rag-tag army.

The village was about to be attacked by mercenaries, he said.

They were trying to take some of the children away, including

his son John. It would be a fight to the death.

The camp advanced to its perimeters,

waiting through the night for an attack that never came.

"We were supposed to kill the person

next to us, if they ran away during the battle," Juanita

Bogue said.

The alarms and attacks were repeated

again and again during coming weeks. Jones told them he was defending

the children.

"This was set up to look like it

was over the custody case of a lot of children. But you had the

feeling it was just over John," said Ms. Bogue.

The tensions in the camp became almost

unbearable, as one white night -- Jones gave the alarms this

name -- followed another.

At the white night meetings, they would

rehearse taking poison. Suicide had become Jones' obsession.

Jonestown also had become a financial

drain. The Social Security checks for the elderly, the checks

for the mentally disabled and veteran's benefits for others came

to $60,000 a month. It wasn't enough.

Members of the People's Temple canvassed

Georgetown for contributions. The Jonestown band played at dances.

Jones still wanted more money.

He finally crawled into the shell of

his house and muttered piteously to his flock over a field telephone

hooked to the public address system:

"I love you. I'm working so hard.

I stayed up for 14 hours for you, doing paper work. I'm weak.

I'm dying. But I love you."

In an already disordered psychological

milieu, the broadcasts of a sick leader were like sandpaper on

ray nerves. And when he emerged from his house occasionally,

the camp was confronted by a man who looked physically healthy

and rested. He would insult and abuse and conduct punishments

for anyone who talked of returning to the states.

"Humiliation from one we love

is much harder to handle than humiliation from an outsider,"

wrote Tish Leroy to her "dad," the Rev. Jones. "Though

I can always justify the lies that get told, I deeply resent

being told them. I understand the end justifies the means.

"The undersurface of me resents

being stifled and stopped in expressing. We are not really allowed

to give honest opinions for these are dictated as policy, and

it is treasonous to have differing thoughts. Yet I can give you

a whole list of 'wrong ideas' I did express to the tune of being

blasted and humiliated for it and told how wrong I was, only

to watch events prove me right. But I grow weary of humiliation,

and am no longer willing to be blasted for honesty."

Ms. Leroy, dissenter, warned Jones that

she would invite confrontation but only at the worst impasse,

only when "there is really a desperate loss endangering

the collective." Then, "I will speak out regardless."

The time undoubtedly came soon.

Ms. Leroy was unusual. People were normally

afraid to be honest with Jones. But the self-analyses were the

one place where they were afraid not to be.

"They thought he could read minds,"

said Jim Bogue, 46, of Suisun. "My kids put me wise to him.

We were planning an escape for two months and they said he sure

as hell would have picked it up. So I realized he couldn't do

it."

It's possible that Jones had just the

opposite trait. He was so wrapped up in his own mind and its

fantasies that he had barely any perception of what his people

were thinking. The self-analyses were his only chance to find

out, to weed out dissent, to calculate his risks.

Toward the end, his risks were growing.

Dissent was running high. By now, he believed that Grace Stoen

had hired mercenaries to attack the camp, and he told people

that bullets had been fired past his head.

Tim Carter, 28, of Burlingame, a farmer

heroin addict who became Jones' "PR" man in Georgetown,

said he was standing beside Jones one day when a bullet whisked

past him.

Jones made plans for leaving. Not alone,

but with everyone.

"He said we had a pretty close working

relationship with Cuba," recalled Mr. Bogue. "He said

we could go to Cuba any time." Any time turned out to be

a few weeks later. "He started loading people onto trucks

to go to the boat. The old folks were supposed to ride in the

trucks and the others were going to walk 15 miles to Port Kaituma,"

she said.

"He was so crazy. Off we went. He

took one trailer load out and the rest of us stood in line for

hours."

The trip was canceled, and the line forming

in the heart of the Guyana jungle for a trip to Cuba broke up

and everyone went back to bed.

Then Jones announced the group was leaving

for North Korea. And then for Africa.

At this point, after a successful life

of drawing thousands of dollars and people to his side, Jones

faced the bitter end. Grace Stoen had drawn attention to his

jungle hell. Rep. Leo Ryan was planning an excursion to Jonestown

and a congressional investigation.

Jones fidgeted and protested the visit.

He wavered, and finally allowed Ryan to enter. It was the end

when he allowed Ryan to walk in the crack the spell.

Jones had known it would happen this

way. A package he'd ordered had arrived the week before Ryan's

visit, and Richard Clark, a laborer, stored it away in the warehouse.

It was a box of cyanide.

Ryan came to Jonestown with a group of

reporters and television cameraman. He stayed overnight, spoke

with campmates, and received an ovation when he observed that

most camp members seemed happy.

But Ryan faced an enemy, not a host.

Jones had decided to have him and the others killed.

The roar of the happy crowd was rehearsed,

the chats with camp members had been carefully staged in advance,

with one camp member playing Ryan and the other playing the role

of a contented citizen of Jonestown.

Even so, people broke ranks when Ryan

was about to leave. Nine of them wanted to leave with him.

"You should have seen Jones. He

offered us money not to leave. Anything. He couldn't believe

it. He begged us to stay," said Ms. Bogue.

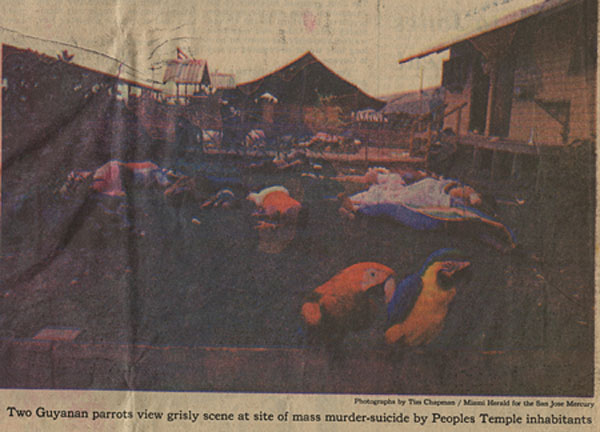

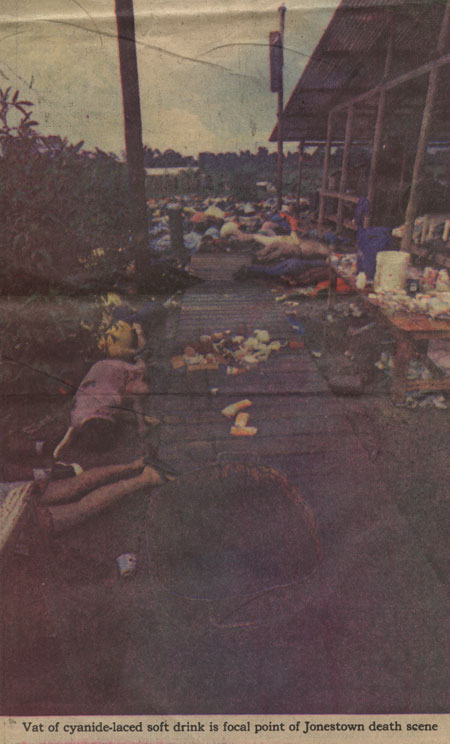

But they left with Ryan and walked directly into an ambush at the nearby airstrip at Port Kaituma. Ryan and four others were killed, and Jones prepared his camp for death. The time had come for the final white night.

Home